Last class was different than usual. We got to conga line over to the other cohort and join forces with them. We voted on subjects we would like to learn about, or that we could teach to others, and then we broke out into discussion groups of our choice. I signed myself up to teach about wild plants, and I was pleasantly surprised – and nervous – to see how many people voted for it! So, I had to, on the fly, lead a discussion on learning and teaching about wild plants.

How I Started Learning Plants

I started my plant-learning journey as an autodidact when I was a teenager. I began as what some call an “armchair botanist” as I would just read books on plant taxonomy and ethnobotany. It wasn’t until one day, when I was looking through a book on fungi ID, that I noticed it mentioned “mycological societies.” I looked into it further and discovered that there was a Vancouver Mycological Society, full of experts, amateurs, scientists, and enthusiasts, who get together regularly for “forays” (group hikes where everyone looks for fungi to ID/talk about/snap photos of) and monthly meetings where speakers deliver presentations relating to fungi. I signed up immediately, and suddenly found that, on the outings with these knowledgeable people, I was suddenly able to confirm the names of all the plants I had read about in books to the real deal in the forest (yep, turns out mycologists know their plants, too!).

Things I recommend for learning and teaching about plants:

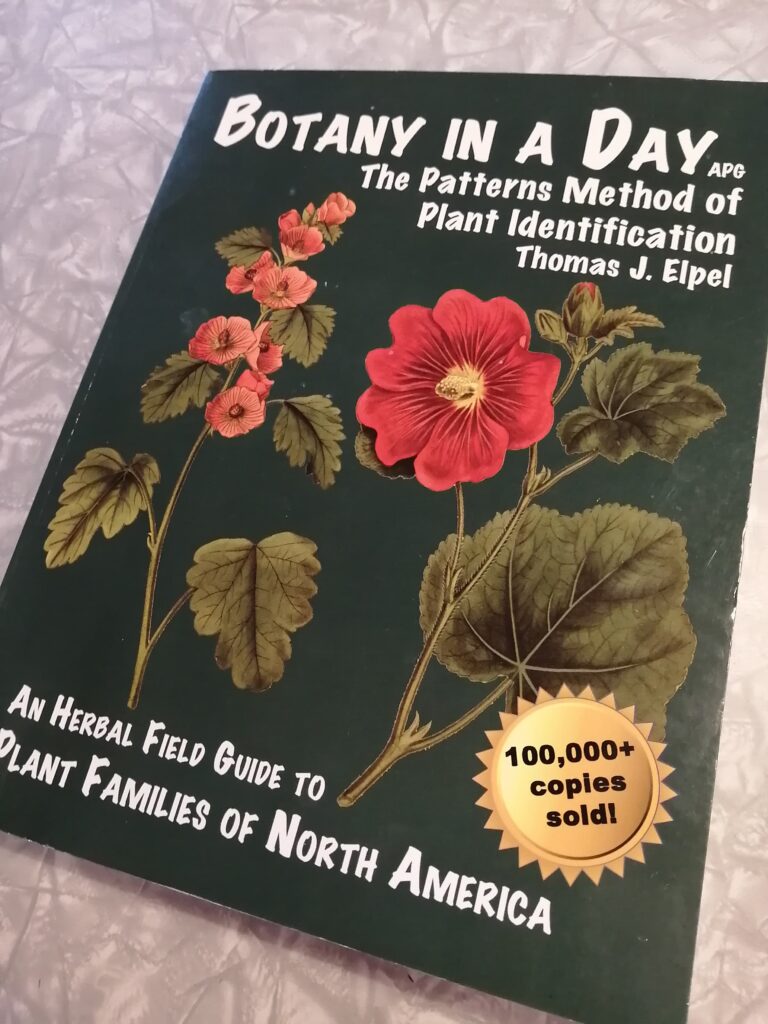

- Start broad: learning plant families can be incredibly useful for narrowing down an ID. Plant families tend to have recognizable patterns. For example, you might look at a flower and determine that it is part of the Brassica family because it has 4 petals with 6 stamens (4 tall and two short). Even if you can’t figure out the genus and species, pinpointing the family is still an impressive feat, and it can tell you a fair amount about a plant as well as help you to begin recognizing patterns. A great book for learning about patterns in plant families is Botany in a Day by Thomas J. Elpel. The book has many families, and I would recommend starting with a few common ones (eg Asteraceae, Rosaceae, Brassicaceae, and Ericaceae might be a good place to start).

2. Look into your local mycological society: When I was younger, I was a prominent participant in the Vancouver Mycological Society (VMS). Locally, I have spent some time (albeit not as much) with the South Vancouver Island Mycological Society (SVIMS). There are so many wonderful, knowledgeable people who attend SVIMS, and many of them know a lot about plants in addition to fungi. In my experience, these folks are more than happy to share their abundance of knowledge.

3. Take photos: when I got into plant ID, I got myself a camera and began snapping photos of plants and fungi. This is useful for many reasons. If you know the ID and any fun facts about the species, you can write that down with the photo (whether its a post on a social media platform, a blog, or even just saved on your computer for personal use); that way, you can spread the knowledge to others, and you can also refer back to it yourself in the future. I myself have experienced a few times in which I was browsing through old plant or fungi photos of mine, and though I didn’t recognize the species in the moment, I had added a tag in the past so that I would never have to forget about the plant! As well, taking photos of plants is useful if you don’t know what the plant is. Many people like plant ID apps; I haven’t tried them personally, though I have heard that they can be hit and miss. Instead, I would recommend (if you are on Facebook) trying a plant ID group. Here, you can post photos you have taken, include the location and any other useful info, and people in the group will comment with an ID and potential useful info. There are many groups out there, but this one might be my favorite. Try checking out groups for fungi ID, too, if you’re interested!

4. Bring nature education into the classroom: many schools are beginning to place an importance on having garden areas. If you can, gardening with your students is an amazing experience. This opens up possibilities for many possible lessons: how to plant, harvesting, seed saving, edibility, companion planting, composting, etc. If you don’t have access to a garden space – not to worry! You can always grow plants inside with your students and have discussions about plant needs, what helps them grow, growing plants from food scraps, etc. If neither of these suggestions are suitable for your class, perhaps you can consider a field trip to a nature spot which can prompt some conversations about the surrounding plants and/or ecosystem. This could be done if you are able to learn about wild plants and feel confident leading a field trip, or you can talk to your school admin to find out about any potential opportunities to have a guest naturalist guide a field trip.

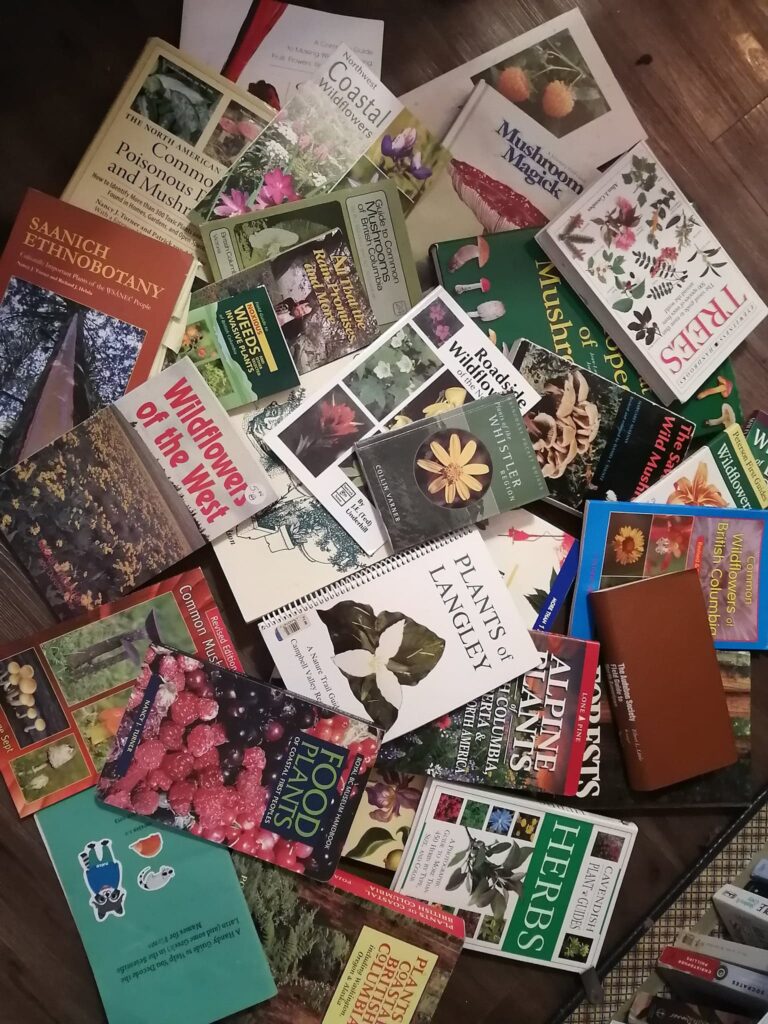

And one last thing – books, books, books!

I can’t stress enough how much books were my best friend when I was first getting into plant ID. Sometimes, when I was out on a foray, I would see an interesting, rare plant, and wonder what it was. In many instances, I would have a faint memory of a plant name come into my mind, I would look that plant name up on Google, and I would see that the image results would match with the interesting, rare plant I had seen. This is thanks to reading so many local plant ID books (yes, make sure they are very local! don’t get Canada-wide books!) and seeing many images of plants with their names attached.

Thanks for reading! Please comment if you have any questions about plants, fungi, books, or anything related to this post! Happy plant hunting 🙂